Millicent Farrar died beautiful. Her hair was the luminous color of mimosa honey. Her color-enhanced eyebrows were two flawless arches. A series of microscopic navy blue dots tattooed millimeters a…

Source: CRIME AND CROISSANTS

Millicent Farrar died beautiful. Her hair was the luminous color of mimosa honey. Her color-enhanced eyebrows were two flawless arches. A series of microscopic navy blue dots tattooed millimeters a…

Source: CRIME AND CROISSANTS

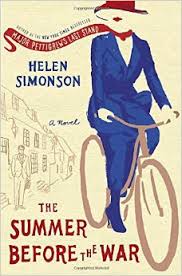

Helen Simonson’s THE SUMMER BEFORE THE WAR begins gently, the way good stories and good music do. Its opening paragraph situates young doctor Hugh Grange, one of its main characters, in the lovely English landscape, “The town of Rye rose from the flat marshes like an island, its tumbled pyramids of red-tiled roofs glowing in the slanting evening light.” Such an introduction is at odds with rules designed to confine contemporary fiction to a straight jacket dreamt up by academics with too much leisure and not much imagination. According to these rules, contemporary readers must be hit between the eyes with an opening sentence that dazzles them to the point of disorientation. Place and time are vague. Readers must work for entertainment. Sentences must be short, adjectives and adverbs must vanish and nouns that have the vaguest etymological association with Latin are forbidden. Passive voice is taboo and so the gerund. Hemingway’s clipped journalistic style trumps Dickens and Trollope’s.

Helen Simonson’s THE SUMMER BEFORE THE WAR begins gently, the way good stories and good music do. Its opening paragraph situates young doctor Hugh Grange, one of its main characters, in the lovely English landscape, “The town of Rye rose from the flat marshes like an island, its tumbled pyramids of red-tiled roofs glowing in the slanting evening light.” Such an introduction is at odds with rules designed to confine contemporary fiction to a straight jacket dreamt up by academics with too much leisure and not much imagination. According to these rules, contemporary readers must be hit between the eyes with an opening sentence that dazzles them to the point of disorientation. Place and time are vague. Readers must work for entertainment. Sentences must be short, adjectives and adverbs must vanish and nouns that have the vaguest etymological association with Latin are forbidden. Passive voice is taboo and so the gerund. Hemingway’s clipped journalistic style trumps Dickens and Trollope’s.

Fortunately, Simonson rises above such silly directives. She renders the town of Rye and people as timeless and universal. There is a special alchemy in that. There is magic firmly rooted in British literary tradition. Shakespeare, Dickens, Jane Austen, had the gift to tell stories that transcend time and place. So does Simonson. Her characters range from those burdened with the prejudices of their place to those ho can break free from parochial morality and outdated conventions. Well-traveled, well educated, forward thinking Beatrice Nash, is one of the latter. Eager to escape the humiliating confines of the aristocratic household of a domineering relative, she accepts a teaching job at Rye. There she meets Hugh Grange, who has been tutoring underprivileged boys while he spends his summer vacation at the home of his aunt Agatha Kent. She also meets Hugh’s cousin, poet Daniel Bookham, an effete poet who is the perfect foil for the level headed young doctor. The three become Beatrice’s friends and supporters.

Beatrice moves into Mrs. Turber’s house, a woman of Dickensian narrow mindedness. In time, she meets the local social leaders, the wannabe social leaders, and the local outcasts, personified by a Roma family. Add to that mix Belgian war refugees and the sweet Sussex summer acquires an entirely different flavor. This is a change that Simonson handles with exquisite deftness. What seems, at first, no more than a good read in the style of Barbara Pym, deepens into a study of social conditions and their effect on the life of minorities—the Roma—and the powerless—women. But this is done without preachy condescension. As the story moves from tense peacetime to war, Simonson’s theme darkens. Effete Daniel’s sexuality comes into question, solicitor Poot, another Dickensian character, reveals his ambitions, a newly arrived couple of writers hits Rye’s brick wall of prudery, Agatha Kent discovers the limits of her tolerance. The Roma boy for whom Beatrice has such hopes learns that the scholarly life to which he aspires is barred to him. A Belgian refugee whose beauty initially gains her the approval of townspeople soon confronts a crisis that nearly turns her into an outcast.

ut these are nothing but the bones of the story. The real thing is richer and far more enjoyable. It is well constructed and enlightening though it never attempts to bludgeon the reader. Rather, it relies on unaffected simplicity. This is superior writing by a gifted author. It is a work I want to keep close as I keep those of Dickens and Trollope. It is work to which I will return after I recover from having my heart wrung by sadness of the awful war that sundered Hugh, his cousin, and so many Sussex boys from their golden landscape where, in summer, “…the bluffs were a massive unbroken line of shadow from east to west, the fields breathed out the heat of the day, and the sea was a slate silk dress.”

In my opinion, fiction writers rarely choose stories. I believe that more often than not, stories that demand to be told choose someone to tell them. Surely neither Andrew Vachs, Patricia Cornwell, nor other novelists whose works ooze blood and gore derive much pleasure from imagining vicious killers and their deeds. Publishers do derive pleasure from profits and readers there are who enjoy putting money into the pockets of writers and publishers of gory novels. This seems to be a symbiotically cozy arrangement for those involved.

Trouble is that some readers lack whatever it is that makes reading gory stories enjoyable. I am one of those. My view of the world is sufficiently dark–what with ISIS and other mad people creating mayhem globally–that do not I find side trips into the minds of imaginary psychopaths all that entertaining. That is why I see M.J. Arlidge’s THE DOLL’S HOUSE and Fiona Barton’s THE WIDOW as fiction to avoid. The former follows the ghastly doings of a criminal who abducts and starves young women. The later deals with a poisoner and a policewoman who likes to be brutalized. I cannot go into details. I stopped reading both books after the first few chapters.That no doubt disqualifies me from judging them fairly.But the problem is not the writing. Rather, it is the topic I find unapproachable. all masterfully crafted, Having read Nabokov’s LOLITA, John Fowler’s THE COLLECTOR, and Emile Zola’s THERESE RAQUIN, I lean into the universal privilege of readers, that which allows me to refrain from diving into the garbage pit of fictional criminals’ mind. I feel no compulsion to read pedestrian writing about fictional killers just so that I can say with satisfaction that there but for the grace of god go all of us. Writers may abdicate the responsibility of choosing their topics. I, as a reader, cannot. My time is finite, unlike the activity of writers and publishers. No, I will leave these two novels to those who are capable of appreciating them. I certainly cannot.

Click on the link hear samples from Kobi’s album.

LUCKY SOUTHERN WOMEN is a Propertius Press book.https://propertiuspress.wordpress.com/about/

Review of Susannah Eanes’s LUCKY SOUTHERN WOMEN and interview with author.

Interview with Jason Goodwin, author of the Yashim crime novel series. We will be talking about his YASHIM’S ISTANBUL COOKBOOK.

NOTE: Diana Darrow mentions Stefania Campo’s I segreti della tavola di Montalbano: Le ricette di Andrea Camilleri as a source of the inspector's food faves.

Last year I got a flock of chickens. In retrospect, to commit myself to care for living beings while the love of my life was dying, was a risky enterprise. At the same time, it was a necessary act, an affirmation that the catastrophe visited upon us would not permanently wither my heart. My beloved was very much in favor of my decision. He wanted me to savor countless joys for myself and for him. Watching the day-old peeps grow into pullets delighted him. It reassured him that I would have something he was about to lose–continuity.

Throughout the year, I endured many losses. A raccoon broke into a temporary coop and slaughtered several of the chickens. My adorably eccentric old cat died. Though these may seem to be tiny dramas, they loomed large in my world. I did not know than that they were but a dress rehearsal for the greater tragedy–the death of the man who had been my friend, my lover, my family, my source of passion and joy.

How I traveled from that autumn to current one mystifies me. Old friends told me that they marveled at my strength. Oddly, I did not feel strong at all. In the privacy of my bedroom, raged, I wept, I cursed fate. My body rebelled at so my much grief and sent distress signs I could not ignore. I had a couple of anxiety attacks that landed me in the emergency room. My glucose levels rose alarmingly. Driving anywhere gave me–and still does–palpitations. Worst of all, I became unable to read all but a few paragraphs at a time. Even now, much to my annoyance, my concentration flags after a short chapter, no matter how well written. My own writing become a dreaded chore. Entries in the blog where I used to publish book reviews dwindled to zero. Somewhere, somehow, I misplaced my life long love for the written word. Two novels I had barely started continue to languish. Correspondence is limited to short e-mail messages.

Lest this become an endless jeremiad, I want this autumn to be a season of good beginnings. That is the reason for this new blog. I want to live up to the promise I made to my beloved–I want to be happy for both of us. I want to leave evidence of my passage through a world that still imbues individual experiences with a certain universality. So much of I experience goes unrecorded because I tend to think that my life is too ordinary.I want to challenge that assumption. No life is ordinary. I want this blog to be a modest signpost to the extraordinary uniqueness of being alive, of surviving grief and moving on to joy. Ideally, want it to be a modern equivalent of Neolithic images that say, “I was here, I was present in my own life.” Unlike those who painted aurochs on rock walls, I have this miracle, the internet. I understand that nothing ever vanishes from cyberspace, so it is possible that a century from now someone will stumble upon my blog entries and learn that essentially, I was not that much different from his contemporaries–yet I was, as every human being is, ordinary and unique at the same time.